CHINA DEFIES VATICAN DEAL IN BISHOP APPOINTMENTS

Recent developments reported by AsiaNews indicate that on April 28 and 29, two priests — Fr. Wu Jianlin and Fr. Li Jianlin — were selected as bishops for the dioceses of Shanghai and Xinxiang, respectively. These appointments, carried out by the Chinese state-controlled “Patriotic Catholic Church,” directly contravene the terms of the confidential agreement brokered between the Vatican and Beijing in 2018, and quietly renewed in subsequent years — most recently in 2024.

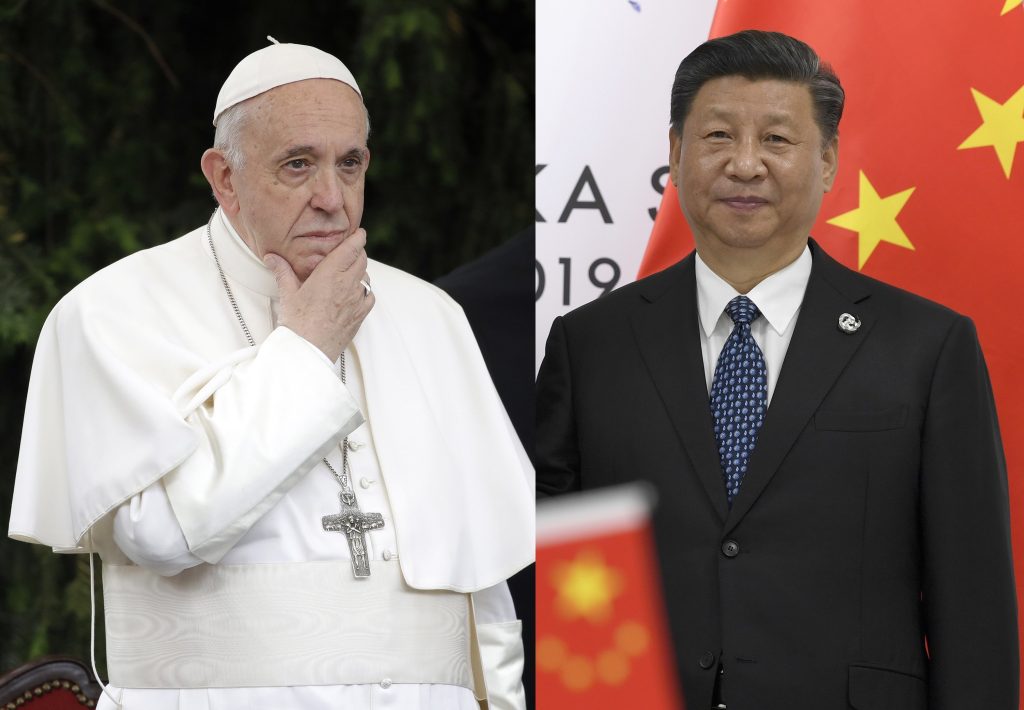

Although the full details of this pact remain undisclosed, it is understood that it grants the Chinese Communist Party the prerogative to nominate bishops, while theoretically reserving for the Pope the authority to approve or veto those choices. Despite this supposed balance, recent events reflect a clear breach of the accord, with the Vatican left sidelined.

A BREAK FROM HISTORIC POLICY UNDER POPE FRANCIS

Previous pontificates, including that of Benedict XVI, consistently rejected any formal compromise with China, arguing that such arrangements would undermine core ecclesiastical principles and Catholic doctrine. Historically, Rome opposed Beijing’s unilateral control over episcopal appointments, emphasizing that legitimacy must come from papal mandate — not state fiat.

Under Francis, however, this firm line appears to have softened. Critics argue that this shift has left members of China’s underground Catholic community exposed and vulnerable. Since the agreement was signed, there has been a documented uptick in state harassment, with clergy and faithful alike subjected to surveillance, arrests, and ideological re-education efforts.

THE VATICAN’S SILENCE AMID REPRESSION

The Vatican’s official media channels have downplayed or outright ignored reports of religious repression in China. Notably, in 2022, VaticanNews referred to Cardinal Joseph Zen’s protests as claims of “alleged persecution.” Even as Cardinal Zen faced trial, Pope Francis declined to comment substantively or even meet him, offering only vague remarks about China’s “complexity.”

This marked a sharp departure from earlier Vatican approaches, which had included vocal condemnation and diplomatic pressure in response to China’s religious policies.

THE SIDELINING OF CHURCH LEADERS OPPOSED TO CHINA TIES

When Benedict XVI entrusted Cardinal Ivan Dias with overseeing evangelization efforts, he counterbalanced Dias’s pro-China leanings by naming Archbishop Savio Hon Tai-Fai — a known ally of Cardinal Zen — as Secretary. However, Hon was removed from his influential post in 2017, just before the agreement with China was signed. He was later reassigned to Greece, and a Jesuit figure more aligned with the Chinese government, Stephen Chow, rose to prominence in Hong Kong.

This personnel shift suggests a calculated alignment with Beijing’s preferences, consistently removing voices critical of Communist Party control over Church affairs.

THE CHURCH’S ALIGNMENT WITH BEIJING’S AGENDA

The Vatican’s accommodation of China mirrors a broader trend in which global institutions have shown increasing deference to the Chinese regime. Since Xi Jinping consolidated power in 2018, Western democracies — and now the Church — have largely avoided confrontation.

Some analysts argue that the Vatican’s cooperation may have involved financial incentives. Dissident Guo Wengui has alleged that the Holy See receives over a billion dollars annually from the Chinese government — a claim that, if true, would raise troubling questions about the Church’s independence and motivations.

RELIGION AS A TOOL OF THE STATE

The bishops installed by the Patriotic Church are seen not as shepherds of faith but as instruments for promoting Chinese ideology among believers. From Beijing’s perspective, religion is acceptable only if it conforms to state doctrine.

This dynamic was evident at a 2024 religious conference in Rome, where Shen Bin — appointed by both the Chinese authorities and later Pope Francis — emphasized the Church’s role in aligning with China’s “national rejuvenation.” By contrast, his predecessor, Thaddeus Ma Daqin, was punished and placed under house arrest for rejecting the Patriotic Association on his ordination day.

Shen Bin’s rise also reflects support from influential Western organizations like the Community of Sant’Egidio, whose ties to government funding and globalist interests have long sparked concern among traditional Catholics.

THE PUSH TO “SINICIZE” CATHOLICISM

Shen Bin has publicly embraced efforts to reshape Catholic identity using Chinese cultural motifs. This includes incorporating traditional architecture, music, and philosophy into Church life — not as an act of organic inculturation, but as a political project to ensure religious compliance with state goals.

This redefinition aligns with views published in La Civiltà Cattolica, where Jesuit sinologists have argued that religions in China must adapt to state-defined cultural narratives, rather than remaining independent or universal in nature.

CHINA’S ROLE IN GLOBALIZATION AND ITS INFLUENCE ON THE VATICAN

In the evolving architecture of globalization, China has emerged not just as a participant, but as a pivotal force shaping the ideological and technological frameworks of the emerging world order. This ascent is not happening in isolation—it is closely aligned with the ambitions of a transnational elite intent on reshaping global governance through centralized control, technocracy, and surveillance. Events like the 2023 “Summer Davos” meeting in Tianjin, which brought together over 1,500 global leaders, exemplify this growing synergy between authoritarian governance models and the objectives of Agenda 2030.

China’s role in this transformation is instrumental. Its government serves as a working prototype for the sort of totalitarian oversight that global technocrats would struggle to impose in liberal democracies. Innovations such as social credit systems, central bank digital currencies, and the hyper-monitoring of individual behavior—already normalized in China—are now being eyed for broader application. Through partnerships with Western institutions, China is also advancing controversial agendas in agriculture (e.g., synthetic foods and GMOs), resource privatization, and artificial intelligence.

From the perspective of these elites, Western democracies must surrender certain civil liberties to match China’s efficiency. Religious restrictions, for example—long a hallmark of Beijing’s domestic policy—are increasingly mirrored in the West through censorship, digital regulation, and ideological policing.

THE GREAT RESET: A SHIFT IN GLOBAL POWER

Without China, many cornerstones of the so-called “Great Reset”—such as financial centralization, digital infrastructure, and the weakening of Western traditions—would be difficult, if not impossible, to realize. The restructuring of global industry, often framed as “decarbonization” or “green transition,” is less about environmentalism and more about economic displacement. Many critics argue that this serves to undermine Western economies and cultures—especially those rooted in Christian moral traditions—while empowering technocratic states like China.

As Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI) warned in a 2000 address, reducing humanity to data points in a system governed by machines is dehumanizing. He likened such processes to the logic of totalitarian regimes, where individuals are valued not for their humanity, but for their functionality. He contrasted this with a Christian worldview, in which every person is seen and loved individually by God.

Ratzinger’s theological clarity and resistance to technocratic agendas stood in stark contrast to what some see as the Vatican’s recent drift toward globalist priorities—including support for population control, digital identity systems, and certain ideological movements under the banner of “inclusion.”

BENEDICT XVI VS. FRANCIS: A CONTRAST IN VISIONS

The pontificate of Benedict XVI was marked by a strong defense of Catholic doctrine and skepticism toward political ideologies that diluted Church teachings. He was adamantly opposed to any arrangement with China that did not affirm the Holy See’s full spiritual authority. In contrast, Pope Francis’ tenure has seen a significant pivot. Many reforms introduced under his leadership—including those related to gender ideology, environmentalism, and global health governance—align closely with progressive globalist values.

This divergence has led to speculation that Benedict’s resignation and the rise of Francis were influenced by external forces seeking a more cooperative Vatican. According to leaked communications and investigative reports, figures like John Podesta had openly discussed strategies to push the Church in a more liberal direction, even suggesting a kind of “Catholic Spring.”

THE CHINA CONNECTION AND THE SECRET DEAL

Among the more controversial chapters of this story is the role played by now-defrocked Cardinal Theodore McCarrick, who visited China repeatedly in the early 2000s and acted as a backchannel between Beijing and the Vatican. His efforts reportedly laid the groundwork for the 2018 Sino-Vatican agreement—a deal whose full terms remain secret but which effectively allowed China to nominate bishops, with only nominal input from the Pope.

McCarrick’s involvement in this process is deeply troubling given his later exposure as a serial abuser. His interactions with high-ranking Chinese officials, including those in charge of religious affairs, raise questions about how the Vatican’s policy on China was shaped—and whether it was compromised by political, financial, or even blackmail pressures.

Numerous observers have noted the stark difference in approach between Benedict XVI’s hands-off stance and the active diplomatic engagement pursued under Francis. Between 2006 and 2013—the bulk of Benedict’s papacy—McCarrick’s visits to China appeared to halt, only to resume shortly thereafter.

THE “DEEP CHURCH” AND THE “DEEP STATE”

For critics, this convergence of interests between certain factions within the Church and global political actors signals a deeper alignment: what has been termed the “deep church” working in tandem with the “deep state.” Both, it is argued, are working toward a centralized global order where traditional institutions are replaced with bureaucratic mechanisms, stripped of moral or spiritual authority.

This theory gains traction when one considers how resistant voices within the Church have been marginalized. Clergy loyal to underground Chinese churches or critical of the Chinese Communist Party have been sidelined, while appointments increasingly favor those willing to cooperate with the regime.

PAROLIN, ZUPPI, AND THE FUTURE OF THE CHURCH

Cardinal Pietro Parolin, the Vatican’s Secretary of State, has been a central figure in these negotiations and has frequently appeared at elite gatherings such as the Davos Forum, the Bilderberg Conference, and various UN climate summits. His openness to collaboration with secular powers—including Beijing—has made him a favorite among those pushing for a more “modernized” Church.

Likewise, Cardinal Matteo Zuppi, associated with the influential Community of Sant’Egidio, has backed the Vatican’s China policy. Both Parolin and Zuppi are considered potential successors to Pope Francis, and their positions on China will be closely scrutinized in any future conclave.

With the Chinese government recently appointing two bishops without Vatican approval—again in defiance of the 2018 agreement—the silence from Church leadership has raised alarms. Critics argue that unless the full text of the secret accord is released before the next papal election, the Church risks entering a new era of diminished sovereignty and spiritual compromise.

CONCLUSION

At the heart of this unfolding crisis are the millions of Chinese Catholics who continue to suffer under a regime that denies them the right to practice their faith freely. Their quiet perseverance stands in stark contrast to the Vatican’s silence—silence that many interpret as complicity. The Church that once gave voice to the oppressed now risks aligning itself with powers that seek to subvert its mission and identity.

The successors of Pope Francis—most notably Cardinals Pietro Parolin and Matteo Zuppi—appear committed to maintaining close ties with global political forces. Their approach suggests a vision of the Church as a nationalized institution, one that mirrors China’s state-controlled model. This vision aligns not only with the principles of authoritarian governance but also with the synodal structure promoted by Francis, which critics see as a means of centralizing power under the guise of decentralization and dialogue.

The original preparatory documents for the Second Vatican Council once proposed a firm denunciation of atheistic materialism. That condemnation never came. The failure to confront Communism with moral clarity—by Popes John XXIII and Paul VI in particular—has had enduring consequences. It opened the door to a new era of engagement that, while politically strategic, lacked the prophetic courage expected of the Church. Today, we are witnessing the fruits of that compromise: a Church navigating its relationship with authoritarian regimes at the expense of its persecuted faithful.

History offers warnings. The decisions made during the 1958 conclave, which led to the election of Pope John XXIII, reshaped the Church’s posture toward Communism. That moment of political calculation over spiritual confrontation remains relevant as the Church again faces choices with far-reaching implications.

What is at stake now is more than diplomatic strategy—it is the integrity of the Church itself. The emerging alliance between the Chinese Communist Party, global technocratic elites, and segments of the ecclesiastical hierarchy represents, in the eyes of many, a betrayal of the Church’s spiritual mission. Their shared animosity is not directed at religion in a broad sense, but at the fidelity of Catholics who remain loyal to the Apostolic tradition, the Magisterium, and the truth of the Gospel.

The Roman Catholic Church—One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic—is not a state instrument, a political body, or a cultural NGO. It is the mystical body of Christ, founded not by consensus but by divine revelation. In times of confusion and compromise, the clarity of that foundation must be defended—especially when those who seek to replace it offer, instead, the machinery of control disguised as progress.